Websocket Server in Actix Part 1

02/09/2023In this tutorial, I want to show how to build a websocket server in actix. There are two ways of building a websocket server in actix:

- With actors.

- Without actors (Actorless).

As per the actix documentation:

Actors are objects which encapsulate state and behavior and run within the Actor System provided by the actix library.

Personally for me, it was much more interesting building the web socket server without actors. Because I get to understand the inner workings of a websocket server much better. I also have much more control, regarding how I would like to implement the web socket server.

There are both examples of how to build a websocket server with and without actors in actix's examples GitHub repo (with actors and without actors). But in this tutorial, I'm going to show you how to build them without actors.

Let's start by making a new project.

$ cargo new rust-websocket-tutorial $ cd rust-websocket-tutorial $ cargo run

Getting a healthcheck running

We're gonna start by adding some of our dependencies

$ cargo add actix-web log env_logger

The first dependency here is just the actix web framework, the second and third dependencies are for logging, which we can use to debug the server if we like. We can use the following setup for our healthcheck.

A healthcheck is a good way to start since, it let's us know that our project is running as is, without worrying about some other stuff, like whether we've setup the websockets properly. It gives us confidence that from here, there is nothing wrong with our web socket server.

use actix_web::{HttpServer, App, web, Responder}; async fn healthcheck() -> impl Responder { "rust-websocket-tutorial is live" } #[actix_web::main] async fn main() -> std::io::Result<()> { env_logger::init_from_env(env_logger::Env::new().default_filter_or("info")); let port = 5000; log::info!("rust-websocket-tutorial will be running on http://0.0.0.0:{port}"); let http_server = HttpServer::new(move || { App::new() .service(web::resource("/healthcheck").route(web::get().to(healthcheck))) }) .workers(2) .bind(("0.0.0.0", port))? .run(); http_server.await?; Ok(()) }

Wow, that's quite the code. If you're a beginner in creating rust web applications. Many of the things you see here may not be familiar. So, let's start with the simplest thing we see here. The main function.

#[actix_web::main] async fn main() -> std::io::Result<()> { ... Ok(()) }

Why is the main function written like this? Welp, the short explanation is that this allows futures in rust to be awaited and std::io::Result<()> just basically says that it's possible for the main function to return an error, but if we don't we return a void or in rust we call it a unit. As you can see at the bottom of the main function we do just that.

The first couple of lines inside the main function are pretty simple.

env_logger::init_from_env(env_logger::Env::new().default_filter_or("info")); let port = 5000; log::info!("rust-websocket-tutorial will be running on http://0.0.0.0:{port}");

The first line initially sets the logger to show info logs, the second line sets the port number and the third line logs to the console that the server will be running on http://0.0.0.0:{port}.

Finally, this block of code.

let http_server = HttpServer::new(move || { App::new() .service(web::resource("/healthcheck").route(web::get().to(healthcheck))) }) .workers(2) .bind(("0.0.0.0", port))? .run(); http_server.await?;

All that this piece of code says is to create a web server with the path /healthcheck with the GET method (shown by the web::get() function call) and route that to the healthcheck function, which we defined above our main function. Then the healthcheck function simply says.

async fn healthcheck() -> impl Responder { "rust-websocket-tutorial is live" }

Which just returns some text saying that the server is live. Notice that healthcheck is an async function. It also returns a type that implements the trait Responder, which is automatically implemented for some data types such as strings, see here you can see a full list of types that already implement the Responder trait. At this point you can run it to check if it works by doing cargo run, and hitting the http://localhost:5000/healthcheck endpoint

Adding web sockets

Before we add web sockets, we need to add a couple of dependencies.

$ cargo add actix-ws tokio --features=tokio/macros,tokio/sync merge-streams futures-util

The crate actix-ws allows us to use web sockets in actix without actors, we will be using tokio to message between the user session and the websocket server using their mpsc type (multiple provider single consumer, find out more here). The merge-streams crate and the futures-util crate provides us with some nice utility functions to handle joining different receivers together. This will be handy when we want to handle messages into our session (from the user of the session) and messages from the server (messages from other users or other sessions).

The web socket server.

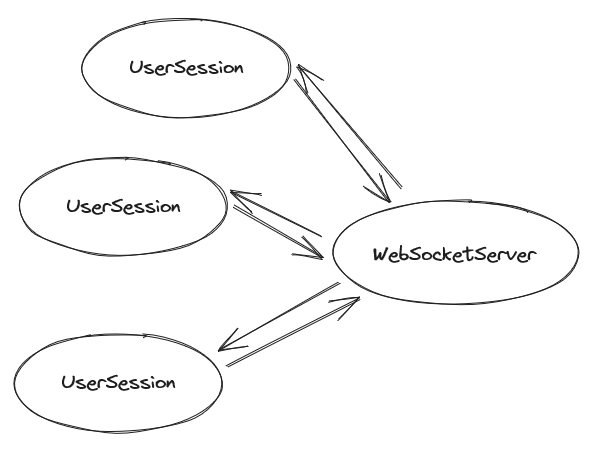

Let's start by creating the web socket server. Our websocket server needs to be able to communicate with active user sessions, we can do this by creating a hash map that associates a user id with the producer side of the

Let's start by creating the web socket server. Our websocket server needs to be able to communicate with active user sessions, we can do this by creating a hash map that associates a user id with the producer side of the mpsc type. With this information, given any user id, if that user id is an active user session, we can send a message to the session using the producer for that session through the web socket server. This is what we are going to work with.

type SessionStore = HashMap<i32, mpsc::UnboundedSender<String>>; struct WebSocketServer { session_store: SessionStore, ws_server_receiver: mpsc::UnboundedReceiver<WebSocketCommands> } impl WebSocketServer { fn new() -> (Self, UserSessionFactory) { let (ws_server_sender, ws_server_receiver) = mpsc::unbounded_channel::<WebSocketCommands>(); let server = Self { session_store: SessionStore::new(), ws_server_receiver }; let session_factory = UserSessionFactory { ws_server_sender }; (server, session_factory) } async fn user_connect( &mut self, user_id: i32, user_sender: mpsc::UnboundedSender<String> ) { self.session_store.insert(user_id, user_sender); } async fn user_sends_message( &mut self, user_id: i32, message: String ) { for (_, user_sender) in self.session_store.iter() { user_sender.send(format!("[UID: {}]: {}", user_id, message.clone())).unwrap(); } } async fn run(mut self) -> std::io::Result<()> { use WebSocketCommands::*; while let Some(msg) = self.ws_server_receiver.recv().await { match msg { UserConnect { user_id, user_sender } => self.user_connect(user_id, user_sender).await, UserMessage { user_id, user_message } => self.user_sends_message(user_id, user_message).await } } Ok(()) } }

So, let's start by explaining the struct definition of the WebSocketServer.

type SessionStore = HashMap<i32, mpsc::UnboundedSender<String>>; struct WebSocketServer { session_store: SessionStore, ws_server_receiver: mpsc::UnboundedReceiver<WebSocketCommands> }

The session_store attribute is just the hash map we were talking about earlier, which associates user id's of type i32 and the producer side of the tokio::sync::mpsc type. The ws_server_receiver is the receiver side of the tokio::sync::mpsc type and provides a way for sessions to communicate to the web server and send messages to other sessions. The WebSocketCommands type is a type that defines what types of messages you can send to the WebSocketServer. I will be using the following definition for the WebSocketCommands type.

enum WebSocketCommands { UserConnect { user_id: i32, user_sender: mpsc::UnboundedSender<String> }, UserMessage { user_id: i32, user_message: String } }

Here, we define two types of messages, the first will notify the WebSocketServer instance when a user connects and contains the user id of the user connecting and it also contains the user_sender attribute which is a means for the server to send messages to the user session, this is the producer we were talking about that we want to store in our HashMaps.

Next there are the methods in our WebSocket server implementation.

fn new() -> (Self, UserSessionFactory) { let (ws_server_sender, ws_server_receiver) = mpsc::unbounded_channel::<WebSocketCommands>(); let server = Self { session_store: SessionStore::new(), ws_server_receiver }; let session_factory = UserSessionFactory { ws_server_sender }; (server, session_factory) }

When creating new sessions, we want each session to be able to communicate with our server. Remember the ws_server_receiver attribute in our WebSocketServer struct definition, well here is where we create that. Then we pass the sender part to the what I call the session factory. The session factory, is just as it's name says creates user sessions for us, by giving each session the sender/producer to our WebSocketServer each session can then send messages to our server.

async fn user_connect( &mut self, user_id: i32, user_sender: mpsc::UnboundedSender<String> ) { self.session_store.insert(user_id, user_sender); } async fn user_sends_message( &mut self, user_id: i32, message: String ) { for (_, user_sender) in self.session_store.iter() { user_sender.send(format!("[UID: {}]: {}", user_id, message.clone())).unwrap(); } } async fn run(mut self) -> std::io::Result<()> { use WebSocketCommands::*; while let Some(msg) = self.ws_server_receiver.recv().await { match msg { UserConnect { user_id, user_sender } => self.user_connect(user_id, user_sender).await, UserMessage { user_id, user_message } => self.user_sends_message(user_id, user_message).await } } Ok(()) }

Then finally we have these three methods. Let's take a look at the run method first. Remember the WebSocketCommand enum we had previously? Well this run function handle's all the different messages that we can possibly receive from the sessions and calls the appropriate method to handle those messages. The user_connect method inserts a user_id and user_sender, which will allow it to send a message to a particular session. While the user_sends_message broadcasts messages to every user connected to the server. And that's it for our WebSocket server. The next thing we need to do is actually implement the SessionFactory that we saw previously as well as implement the UserSession. Which I will write in the next post.

Thanks for reading.